Physiology, Elementary, Voice

Ask a Neuroscientist

Monday, June 22, 2020

at 4:29 PM

There are many occasions throughout the year when we sing in groups: at birthdays, parties, concerts, community gatherings, places of worship, and sporting events, to name just a few. For some of us, however, the prospect of singing in front of others is a less than joyful occasion: A lot of folks tense up at the prospect of singing in front of other people, fearful of how they might sound.

As a singer myself, I’ve always been interested in this question. In one of my first studies, we recruited people of varying abilities to come in to the lab, and measured how accurately they could sing back single notes. Some of them were quite accurate, and some of them less so. Next we asked the same study group to match those same notes, but in a different way. We gave them a slider – a simple device that allows users to match the pitch they hear – and asked them to use the slider to match the notes, instead of their voice. As it turned out, almost everybody could match the pitch on the slider with incredible accuracy – even those who couldn’t do so with their own voice.

What this tells us is that out-of-tune singers don’t generally have any problems perceiving the notes in music. Instead, the issue is one of motor coordination. Most of us can identify the right notes, but our brains have mapped out the wrong vocal output to match those notes. So we hear the right note, but our brain triggers the wrong vocal voice muscle to reproduce it.

In another experiment, we explored the timbre in a voice. First, we recorded people’s own voices. Later that day, we asked them to match those recordings. For this task, people were generally more accurate, but there were still some who couldn’t match the pitch accurately. This still points to a motor coordination problem, but it also shows that for some people, matching a real voice is easier than matching another type of sound.

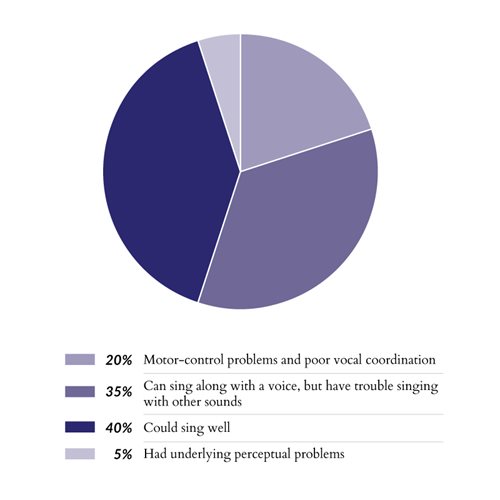

Overall, we found that poor singers had different types of problems:

So, what does this mean for those of us who want to learn to sing better? It means recognizing that singing isn’t just in your head; it’s a physical act. And like other physical acts, such as hitting a serve in tennis or shooting a basketball, practice is the best way to improve. Practicing in a vocal ensemble can be particularly useful, because singing with other voices can make the task a bit easier. But even singing on your own in the shower is a good start.

In my line of research, I hear stories all the time about people who do not sing because in their youth they were asked not to sing — so that they wouldn’t “ruin” a performance. It’s infuriating, because it’s exactly the opposite of what children need to do to get better at singing. Thankfully, most music teachers nowadays take a more enlightened approach, using a process-based, rather than performance-based, teaching style.

But I have met people who have started singing with enthusiasm and happiness (and improvement) even after decades of avoiding it.

Singing is a joyful act, one reason that it’s the centrepiece of so many religious and secular traditions. If you’re ready to embrace singing and make it a bigger part of your life, just go ahead and give it a try!

Monday, June 22, 2020

at 4:29 PM